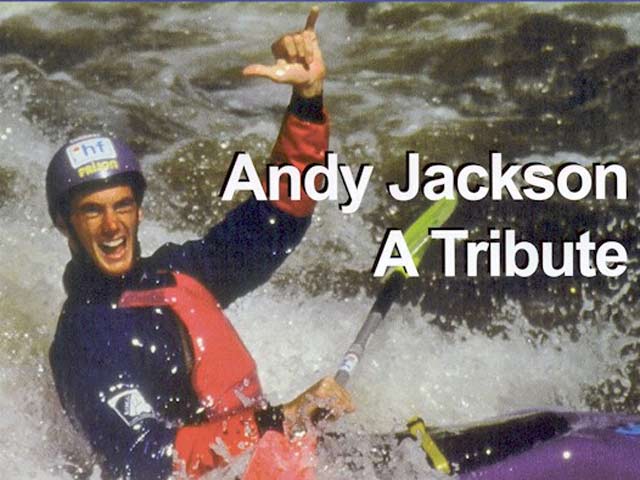

Andy Jackson

Andy Jackson explored the rivers of Scotland and campaigned for free access to them. The Access Fund was set up to continue his work. This tribute was published in 2005 after his death.

May 23 1971 to December 5 2004

The Scottish whitewater kayaking scene has lost its leader Andy Jackson. He died of pneumonia, aged 33, following several years suffering from brucellosis, most likely contracted during kayaking adventures in Asia.

For the previous 10 years or so, Andy had maintained a high profile and a reputation for daring first descents. But his beginnings were like everyone else’s at the time; on flat water in fibreglass boats his parents had got for him ‘to have a go’. Before I knew him, there are pictures of Andy as a gangly young teenager smiling over the cockpit rim of a Snipe or similar, on Loch Lomond. At this time Andy was also a very keen skier, and his initial career aspirations were in outdoor education. It was here, at Ardentinny, that Andy was wisely steered towards Community Education. He got a place at Dundee, and by now had developed the passion and ability in kayaking that he became known for.

Andy spent some years as a self-proclaimed ‘Government-sponsored kayaker’, scraping together only enough money to pay for transport to rivers and, (barely) to eat. When I met him, in 1993, he seemed consumed by the desire to explore white water. At that time, very few others were. Andy scoped out every part of Scotland, getting people to go with him when he could, and going alone when he couldn’t. He maintained a much sought-after (and well guarded) map, with all his descents highlighted and commented on. There were dozens more than the guidebooks showed, and before he was 30 he had made over 100 first descents in Scotland alone.

The joy of white-water is best shared – an aspect of boating that Andy loved. From his happily naive flatmates (running waterfalls in a borrowed Topo Duo) to other good paddlers he might recruit for a mission, there are many people who will remember Andy’s glinting eyes and outstretched arms saying “C’mon, you’ll be fine…”. There often ensued an epic day out in pouring rain on slippery rocks with a gripping heart and fading light. The desire to push on for a second or third river in a Scottish winter day gave Andy one nickname as the Prince of Darkness.

Andy was quite calculating in his approach to risk management though, and deliberately left a wide safety margin. It was very rare to see him in trouble on a river, and he was a great support to others in the group. So many people pushed their own margins when paddling with Andy that he needed to be supportive. Many people including me can recount fearful times, following the back of Andy’s helmet beyond their comfort zones.

During a kayaking trip to the European Alps in 1992, Andy met Bridget Thomas, who became his partner for the rest of his life. Bridget herself was a talented slalom paddler who, after exploring several steep Scottish burns in a Dancer, went on to win the ‘Rodeo Worlds’ in Ocoee. In 1994, Andy and Bridget set off to spend a year following the world’s kayak seasons with me, ‘Goose’. Bridget’s success, and the profile this trip promised, offered Andy’s first real taste of sponsorship from the likes of hf, Prijon and Kogg. It was a fun time, hedonistically pursuing white-water whilst loyally seeking shameless promotional opportunities! The friends and ideas Andy had previously made, particularly in Nepal, were vital to us. Andy’s name opened many doors and introduced us to many great people, from river doyens such as Slime and Dave Allardice to Sherpas and porters who remembered Andy from previous visits.

The way that porters we passed on trails remembered Andy, of all the tall white men who pass through Nepal, is an example of one of Andy’s strongest facets that will be remembered fondly by very many people who will say “I met him once…’ hardly knew him but he felt like a friend”.

Andy was a genuine egalitarian, as happy with someone he’d never met before as he was with the ‘elite’. If he jumped an eddy queue, it was with a cheeky grin meaning ‘ha! Come and join me in there!’ rather than a sense of deserving priority. He had time for everyone and everyone loved him for it. Many people thought of Andy as their best friend.

Andy’s principles inevitably led him into politics and Politics. He was an active supporter of the Scottish National Party whilst at college, renowned for employing his outdoor skills for the cause, and his social skills to gather support. His kayaking politics, in particular his belief in a right of access, took Andy on a wryly amusing course. In 1993, Andy was seen by the Scottish Canoe Association as the “bad boy” of Scottish access negotiations, allegedly responsible for the removal of such famous landmarks as Glen Lyon’s ‘NO CANOEING’ signs. His disarming smile and passive continuation to access the river frustrated several grippy owners of Scottish riverbanks.

In about 1997 Andy came back this time on the SCA’s side as a River Advisor for the Garry. He lent his significant – and now matured – diplomatic weight to discussions with landowners and hydro companies. Not long after this Andy got behind the SCA’s plans for a not-for-profit Scottish whitewater guidebook, the proceeds of which go to promoting access to rivers. With Bridget’s support, he spearheaded a national opening-up campaign amongst paddlers which resulted in one of the world’s best books of its genre, and a lasting symbol of the Scottish whitewater scene’s new unity. For the last couple of years Andy has been working as the SCA’s paid Access Officer, building on his predecessor’s great work and overseeing the practical implementation of world-leading access legislation. Andy’s passion for his work and fantastic relationships with talented friends led to key extensions of the SCA’s website. S uddenly we can access info on river flows across the country, see what hydro dams are planned and how we can oppose them.

The difficulties overcome in doing this are typical of another of Andy’s facets of character. If something appeared to be impossible, Andy would commonly rock back, lock his fingers together and say “well, now, let’s see…” The subsequent debate would almost always reveal a strategy and you would find yourself giving it a go. Andy was hugely optimistic and not easily daunted, and very good at giving other people the confidence they lacked. Some people reading this will be laughing though, as Andy would use the same technique (and mannerisms) to manipulate your conversation round to doing things his way!

After the World Tour of 1994-95, Andy continued to adventure around the world on a more familiar ‘holiday’ basis, from his home with Bridget in Fort William, visiting the Homathko in BC, trips to Norway, Nepal and Chile, and filming in Iceland. He had a genuine love of what he was doing, using sponsorship and notoriety as a tool for more fun rather than an ego prop. In doing so, he was known for an uncanny ability to photograph himself whilst running grade 5! Andy stayed loyal to his sponsors and never missed an opportunity to raise their profile.

At 6’7″ and a very modest weight, Andy was very tall and very skinny. This isn’t a great shape for big waterfalls, and Andy did injure himself. First, his pelvis, then the wrists, then finally brucellosis which reduced his immune system leaving him prone to such common illnesses as ‘flu. This knocked his ability to face cold wet kayaking conditions regularly, but extended his repertoire of passions to paragliding in particular. Despite this, Andy enjoyed key river days and for those of us fortunate enough to have paddled regularly with him, the good days are how he will always be remembered.

Bridget actively supported all of his successes throughout the last 12 years. It’s impossible to praise Andy’s work without recognising her contribution. A wealth of people’s best wishes supports Bridget in this difficult time.

Andy Jackson was Scotland’s most eminent kayaker ever. Andy’s limelight lasted the decade that kayaking took centre stage. He was the emerging leader when there were fewer than 20 Topos in Scotland, and still followed now there are hundreds. It will never be possible again, to do so many first descents in Scotland. Andy was the key instigator of the first comprehensive guidebook, and will have died happy that Scotland has emerged as a world leader in access legislation for ordinary people. Andy’s huge frame matched his huger personality, and without giving lessons he taught everyone he met something frequently life changing.

Andy Jackson is a legend.

This article written by former SCA President Andy England first appeared in the January 2005 issue of Canoeist magazine. It ‘says it all’ about Andy and we are grateful to Stuart Fisher and Andy England for allowing it to be reprinted here.